History of Hymns: “Come, O Thou Traveler Unknown”

By C. Michael Hawn

“Come, O Thou Traveler Unknown,”

by Charles Wesley;

The United Methodist Hymnal, Nos. 386 and 387

Come, O thou Traveler unknown,

Whom still I hold, but cannot see!

My company before is gone,

And I am left alone with thee;

With thee all night I mean to stay

And wrestle till the break of day.

The intercessions, though regretfully often omitted in United Methodist worship, are among the most important parts of the gathered body of Christ. Perhaps the most significant words many parishioners may hear when in worship is the absolution: “In the name of Jesus Christ, you are forgiven!” “Come, O Thou Traveler” captures the pure joy of forgiveness of this moment perhaps unlike any hymn in the English language.

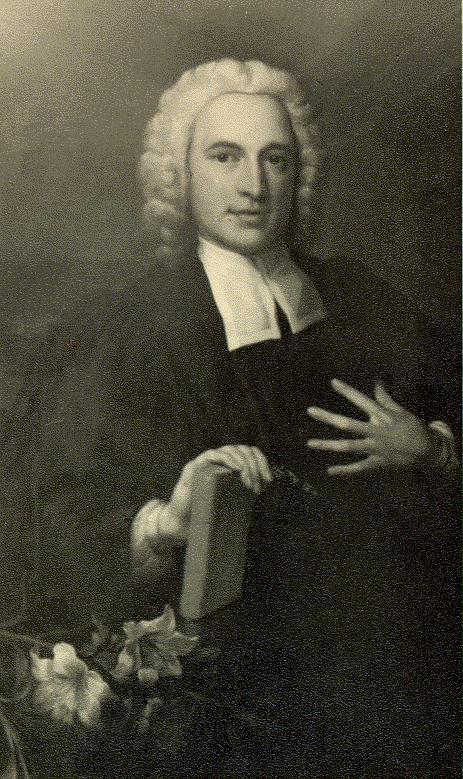

Of the eighteenth-century hymn writers whose hymns are still being sung in the twenty-first century, only Isaac Watts (1674-1748) rivals Charles Wesley (1707-1788) in representation in modern hymnals. Because of its Wesleyan roots, The United Methodist Hymnal (1989) contains more than twice as many hymns by Charles Wesley than Watts. As we shall see, this hymn ranks very high in the evaluation of Watts, often called the “Father of English Hymnody.”

Though it may not be familiar to many readers, “Come, O Thou Traveler Unknown” is one of the most important and, many say, the best of Charles Wesley’s hymns. First published in Hymns and Sacred Poems (1742) in fourteen, six-line stanzas under the title of “Wrestling Jacob,” the hymn is a personal interpretation of the story of Jacob wrestling with the angel of God at Peniel (Genesis 32:24-32). At the end of the struggle, Jacob receives a new name, Israel (Gen. 32:28). As in any Wesley hymn, poetic verse and Scripture are intrinsically linked. The art of this hymn is evident in how Charles Wesley treats Scripture allegorically. By allegory, I mean that Jacob’s spiritual struggle becomes Wesley’s own autobiographical struggle and, in turn, becomes our story.

One may find the entire fourteen stanzas of this classic hymn at 387 (text only) in The United Methodist Hymnal. Four stanzas were selected for UMH 386, the version with musical notation. Stanzas 1 and 2 in the hymn version are stanzas 1 and 2 in the original. Stanzas 3 and 4 in the hymn are the original stanzas 6 and 7 in the longer poem. The original version of the final stanza in the hymn version (stanza 4) bears notice on two points, one of which may be somewhat curious to the modern reader:

‘Tis Love! ‘Tis Love! Thou diedst for me;

I hear thy whisper in my heart.

The morning breaks, the shadows flee,

Pure Universal Love thou art:

To me, to all, thy bowels move –

Thy nature, and thy name, is LOVE.

If one does a search of “bowels” in the King James Version of the Bible, the version that the Wesleys used, it will become apparent that this word appears often throughout the entirety of Scripture. Citing the Oxford English Dictionary, hymnologist J. R. Watson notes that the term “bowels” was quite common in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and “considered as the seat of the tender and sympathetic affections— to mean pity, compassion, feeling, ‘heart’” (Watson, 2002, 183). The other significant aspect of this stanza is that “Wesley’s faith journey, as told through his hymn, ends with the revelation that God is ‘pure universal Love’” (Young, 1993, 295). “Universal Love” is a primary tenet of Wesleyan theology and stood in bold contrast to the Calvinist view of the “elect” propagated by Wesley contemporary and Anglican priest George Whitefield (1714-1770), whose powerful preaching drew crowds that rivaled that of the Wesleys themselves.

The famous Commentary on the Whole Bible (1706) by Anglican cleric Matthew Henry (1662-1714) is said to have influenced Wesley's understanding and interpretation of this passage. Henry sets up the scene with a brief overview of the entire chapter 32:

We have here Jacob still upon his journey towards Canaan. Never did so many memorable things occur in any march as in this of Jacob’s little family. By the way he meets, I. With good tidings from his God (vs. 1-2). II. With bad tidings from his brother, to whom he sent a message to notify his return (vs. 3-6). In his distress, 1. He divides his company (vs. 7-8). He makes his prayer to God (v. 9-12). He sends a present to his brother (vs. 13-23). He wrestles with the angel (vs. 24-32). [www.biblestudytools.com/commentaries/matthew-henry-complete/genesis/32.html]

Examining closely the complete text, it becomes evident how Wesley’s version parallels Scripture. The scriptural narrative begins, “And Jacob was left alone; and there wrestled a man with him until the breaking of the day” (Gen. 32:24, KJV). The opening stanza cited above concludes with a nearly verbatim quotation from this verse. Henry points out that Hosea 12:4 also references this event: “Yea, he had power over the angel, and prevailed: he wept, and made supplication unto him: he found him in Bethel, and there he spake with us” (KJV).

Wesley also draws upon the persistent request found in this passage, “What is thy name?” (Gen. 32:27, KJV) “Tell me, I pray thee, thy name” (Gen. 32:29). In Wesley's hymn, the question is “Who art thou? Tell me thy name and tell me now.” In the complete version, Wesley’s insistence continues through several stanzas: “I will not let thee go till thy name, thy nature know.” The unknown “NAME” is central to this passage. Henry’s commentary notes that there are several interpretations of the “name,” but that “we are sure God’s name was in him,” citing Exodus 23:21: “Beware of him, and obey his voice, provoke him not; for he will not pardon your transgressions: for my name is in him” (KJV).

At this point, it is clear that Wesley is not just writing a scriptural paraphrase, but has merged his own faith struggle into the biblical passage. Wesley's demand to know the name of the one with whom he struggles magnifies that of the biblical narrative several times over through powerful images and repetition.

Keep in mind that during the previous decade before this hymn’s publication in 1742, Charles and John had traveled to America in 1735, a journey that was unsuccessful pastorally, professionally, and personally, resulting in a crisis of faith. It was only after being offered what we might call today “spiritual direction” by Moravian minister Peter Böhler (1712-1775) that Charles experienced his own conversion on Whitsunday (Pentecost), May 21, 1738, following a severe physical illness and perhaps what might be called today, depression. Within a few days, he recorded his conversion in the hymn “Where Shall My Wondering Soul Begin”:

Believe: and all your guilt’s forgiven,

Only believe – and yours is heaven.

While the first half of the extended hymn insists on knowing the “nature” and

“name” of the Savior, the second half exults in the knowledge of the name when finally revealed: "'Tis Love! 'Tis Love!.... pure Universal Love….” Then the poet repeats six times (!), “Thy nature, and thy Name is LOVE”! (Upper case in the original!) This passionate revelation parallels Jacob's (now Israel's) recognition of the one with whom he wrestled: “I have seen God face to face, and my life is preserved” (Gen. 32:30, KJV).

Carlton Young, United Methodist Hymnal editor, notes that the “hymn’s central theme is the intense struggle attendant in the changing of one’s own heart and being” (Young, 1993, 295). British hymn scholar J. R. Watson states: “Wesley is putting himself in the place of Jacob, and encountering God in wrestling with Him as an adversary. As Jacob 'halted upon his thigh’ [32:31], so the redeemed sinner is marked by the encounter to the end of his life” (Watson, 2002, 184). The power of this narrative in its original form lies in what Wesley scholar J. Ernest Rattenbury states is Wesley’s ability to tell the story “as if it were an event of his own experience” (Rattenbury, 1941, 96).

John Wesley cited this hymn in the obituary tribute to his brother at the Methodist Conference in 1788, stating that Isaac Watts had acknowledged “that single poem, Wrestling Jacob, was worth all the verses he himself had written.” Two weeks after Charles Wesley's death, John Wesley, preaching at Bolton, attempted to teach this hymn. He was said to have broken down at the lines in the first stanza, “my company before is gone, / and I am left alone with thee.”

It is worth one’s time to read the entire original fourteen stanzas appropriately printed in The United Methodist Hymnal (387). Upon reading the poem in its entirety, one cannot help but agree with Anglican hymn writer Timothy Dudley-Smith, who states in his commentary in the Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology:

The whole poem is a sustained tour de force in which the spontaneous daring, dramatic emotion and vitality are enhanced by an unobtrusive skill and an astonishing maturity of technique. The 84 lines of the original are remarkable for the urgency and easy flow of the narrative, which yet includes a punctuation mark at the end of almost every line. Similarly the syntax flows with very little inversion. Verses 6, 7 and 8 are also notable for the use of paradox, a feature of much of Charles Wesley’s writing, but rarely so effectively displayed as here.

For further reading:

Dudley-Smith, Timothy. "Come, O thou Traveller unknown." The Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology. Canterbury Press, accessed October 28, 2017, http://www.hymnology.co.uk/c/come,-o-thou-traveller-unknown.

Henry, Matthew. Commentary on the Whole Bible (1706) www.biblestudytools.com/commentaries/matthew-henry-complete/genesis/32.html.

Rattenbury, J. Ernest. The Evangelical Doctrines of Charles Wesley’s Hymns. London: Epworth Press, 1941.

Watson, J. R. An Annotated Anthology of Hymns. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Young, Carlton R. Companion to The United Methodist Hymnal. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1993.

C. Michael Hawn is the University Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Church Music, Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, TX.

Contact Us for Help

View staff by program area to ask for additional assistance.