History of Hymns: "Man of Sorrows! What a Name"

By Jonathan Hehn

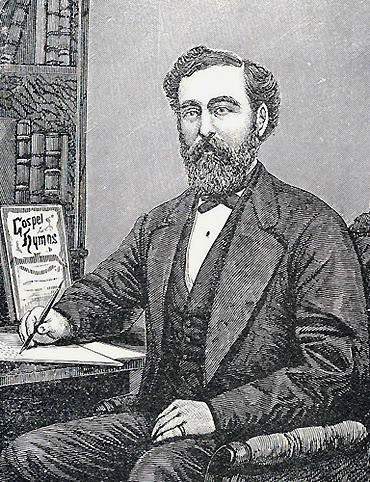

Philip Bliss

“Man of Sorrows! What a Name”

("Hallelujah! What a Savior")

by Philip Bliss;

The United Methodist Hymnal, No. 165

Man of Sorrows! What a name

For the Son of God, who came

Ruined sinners to reclaim.

Hallelujah! What a Savior!

One might be tempted to pass over the hymn, “Man of Sorrows! What a Name,” when planning for Eastertide, given the rather depressing title. Indeed, the editors of The United Methodist Hymnal might have been cognizant of that fact, because when they included it at No. 165, they used its other common title, “Hallelujah! What a Savior.” Yet, especially for those Christian traditions in which cross-centered rhetoric remains strong throughout the year, this hymn can be a marvelous one for the season of Easter. This is the second of four articles in the month of April that will explore hymns especially appropriate for Eastertide.

“Man of Sorrows, What a Name” owes its text and tune to the nineteenth-century hymn writer Philip Paul Bliss. Born in 1838, Philip Bliss was one of the most important American gospel song writers of the century. A contemporary of Dwight Moody, Ira Sankey, and George Root, Philip Bliss made a huge contribution to American evangelical hymnody. The 1907 edition of John Julian’s Dictionary of Hymnology credits him with forty-eight “widely known” hymns, as well as many others.1 Among the hymnals indexed by Hymnary.org, there are currently two hundred forty-seven individual hymns to Bliss’s credit.

Bliss was raised in a farm family in central Pennsylvania and first learned the rudiments of music at the age of eighteen in a singing school run by J.G. Towner. He later attended a convention headed by the legendary musician William Bradbury and over the next few years actively pursued a musical education.2 Eventually his abilities and training as a musician enabled him to become a music teacher in Rome, Pennsylvania. Around that same time he began to become active as a church musician, first in the Presbyterian church in Rome, then as an itinerant music teacher, and in later years as a staff member at the Chicago publishing firm Root and Cady. The Festschrift known as Memoirs of P.P. Bliss records that he wrote his first song at the age of twenty six, and his last at the age of thirty eight, which would mean an average output of about twenty songs per year.3 Julian says that Bliss was originally a Methodist and later a Congregationalist, but his Memoirs tell of a man who claimed no firm denominational allegiance. At various points in his life, both professional and personal, he was associated with Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Seventh-Day Baptists, Disciples of Christ, and others. As with many itinerant music teachers, and many nineteenth-century evangelicals in general, he easily crossed denominational boundaries, sharing his gifts with many churches in the process. Philip Bliss’s life was tragically cut short in 1876, when a railway crash in Ashtabula, Ohio, killed both him and his wife.

As stated above, “Man of Sorrows! What a Name” is also commonly called “Hallelujah! What a Savior!” This is because the text, which is strophic, has at the end of each of the five stanzas the phrase “Hallelujah! What a Savior!” Gospel songs of this and following eras often featured a refrain, but the repeated ending phrase of this hymn is not the same as that. Rather, the repeated text is an integral part of the metrical structure of each stanza. In that way, it is more similar in construct to the ancient German “Leise,” a type of folk hymn in which each stanza ends with the text “kyrieleis’” (“kyrie eleison”). As might be expected with a text borne of any nineteenth century revival movement, “Man of Sorrows” is full of the language of sin and redemption. In particular, the second and third stanzas utilize strong sacrificial language when speaking of the atoning death of Jesus Christ:

Bearing shame and scoffing rude,

in my place condemned he stood,

sealed my pardon with his blood:

Hallelujah, what a Savior!

Guilty, helpless, lost were we;

blameless Lamb of God was he,

sacrificed to set us free:

Hallelujah, what a Savior!4

The wonderful and immensely useful thing about this text, though, is how it continues. Beginning in stanza four, “Man of Sorrows” moves beyond the death of Christ, into his resurrection, ascension, and second coming. In so doing, it traces the full narrative of the pascha, not simply stopping with the cross, but allowing the exaltation and reign of Christ to literally have the final word. Ending each of these final stanzas, of course, continues to be found the acclamation of praise, “Hallelujah! What a Savior!”

Many congregations, both United Methodist and otherwise, have intentionally recovered a richer observance of the liturgical year, including the discipline of burying the word “hallelujah” during Lent. For such communities, this practice provides an opportunity to use “Man of Sorrows! What a Name” in a liturgical way, perhaps introducing it during the Easter season as a way of recounting the entire paschal narrative as the Church approaches Ascension and Pentecost, while also simultaneously providing a text full of the once-buried word “hallelujah.”

This hymn provides yet another opportunity as well. There has been a recent trend, mostly among congregations practicing various emergent modes of worship, of re-tuning and/or simply recovering unaltered hymnody of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For these congregations, which are most often evangelical, “Man of Sorrows! What a Name” provides a good opportunity to sing about the full breadth of the paschal narrative. Bliss’s tune for this text is both accessible and easily adaptable. One might easily arrange it for a guitar-based ensemble, and the rhythmic, almost march-like style of the tune is well suited to the use of percussion.

Though worship planners might be tempted to pass over a hymn like this because of its strong atonement language or occasional archaisms, it is a hymn worth giving a second look. Indeed, it is still being published in hymnals today, as editorial boards see both the usefulness of the text and the strong simplicity of Philip Bliss’s tune. As you plan your Eastertide hymnody, make time to sing this hymn, a very useful and noble piece of American hymnic history.

2 ed. D.W. White, Memoirs of Philip P. Bliss, New York: A.S. Barnes and Company, 1877. p. 19ff Available online at https://books.google.com/books?id=dh7PAAAAMAAJ&dq=memoirs%20of%20p.p.%20bliss&pg=PA19#v=onepage&q&f=false

3 Memoirs, 31-32.

4 This version of the text was taken from the main (“Authority) page on this hymn at http://www.hymnary.org/text/man_of_sorrows_what_a_name. From there, one can explore the many small variants of this hymn text. Some hymnals omit the third stanza altogether, perhaps because of its strong atonement language.

About this month’s guest writer:

Jonathan Hehn, OSL, is a Presby-Lutheran musician and liturgist currently serving Good Shepherd Lutheran Church and Saint Leo University in Tampa, Florida. He is a passionate practitioner, writer, and thinker.

This article is provided as a collaboration between Discipleship Ministries and The Hymn Society in the U.S. and Canada. For more information about The Hymn Society, visit thehymnsociety.org.

Contact Us for Help

Contact Discipleship Ministries staff for additional guidance.